Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffeeThere are many situations which can cause unavailability. One of them can be a bug in a software, bad architecture design decisions or even a human error. Depending on how the numbers are calculated, from 22% to even 70% of outages are caused by human error. Software engineers, DevOps or administrators cannot prevent all the outages but we can learn from ourselves to improve the stability and reliability of systems we are creating. In this article, I will present how Brainly learns on his mistakes to improve the stability and latency of its infrastructure.

At a big scale, you have to deal with more than one server because only one machine cannot handle huge traffic and vertical scaling becomes unprofitable. The more machines you have at your disposal, the greater the chance that something will go wrong. Failure is inevitable and it’s only a matter of time when it will happen. Our responsibility is to make sure that we are ready for such situations.

RabbitMQ outages

RabbitMQ is the heart of our platform. Most of our microservices produce or consumes events using this event bus. Within a week, we had 3 outages of our RabbitMQ cluster from 3 different reasons. We learned that even though RabbitMQ supports high availability some unexpected situations still may happen and cause its downtime.

During maintenance, we added a new parameter to RabbitMQ configuration. Unfortunately, by mistake, we lead the configuration to the invalid schema. A person who reviewed the change did not notice the mistake and the configuration was applied on production RabbitMQ cluster.

The mistake was noticed very quickly and the patch was deployed as soon as it was possible but it led to the outage of the whole cluster for about 20 minutes. We had no automatic checking the configuration on a development environment and this is what we fixed.

One week later, when our traffic started growing we decided to scale the RabbitMQ up. We increased the number of nodes from 3 to 9 and replaced old nodes. It wasn’t possible to simply changing the number of nodes because the “old” nodes were running Ubuntu 14 which is quite old now. The update required their reinstallation. Every new node was added selectively to the cluster. After forming a properly running cluster, we started removing the old clusters one by one. The cluster was running without any errors, our monitoring was not showing any abnormal behavior of the RabbitMQ cluster so we assumed that cluster was running correctly without any downtime. After a while, one of our developers noticed that his micro service stopped publishing events. A quick investigation showed that queues disappeared. All of the microservices was restarted and after the restart, everything went back to normal. But what did actually happen?

We’re developing a library written in Go which helps us deal with events - Fred. Unfortunately, Fred did not react on the RabbitMQ’s structure change and tried to use non-existing nodes. Fred should notice the change and update the available node’s list. But it did not. We fixed the bug quickly to prevent similar situations in the future. Unfortunately, it wasn’t our last RabbitMQ outage.

A few days later, one of RabbitMQ hard disk refused to obey. When the damaged node was removed from the cluster, another node experienced the same hard disk failure. To keep the quorum, we started node recovery.

When the node was back in the cluster it was unable to process any request. After a few attempts to bring back the broken node, the whole cluster of RabbitMQ crashed and each node started working independently. To prevent losing messages, our DevOps decided to restart the whole cluster. This operation solved the problem and everything went back to normal.

What did we do to prevent similar problems in the future?

RabbitMQ is only an example of a dependency which can become unavailable at any time. It can be a database server, Varnish installation or even the whole Kafka cluster. Because we treat our job very seriously, we decided to find out the best possible solution to prevent similar situations in the future. Fixing software bugs is a short-term solution but we certainly had some issues in the architecture. We write an outage note every time when something goes wrong to be able to come back to our experiences later.

We needed a tool to help us find the root cause generate ideas for the long-term solution. The choice fell on System Design.

System Design is a brainstorming type of session which helped us to find solutions for problems we faced, that is: cascading failures and improving operations in case of the network partition, resulting in weekly 99.99 uptime.

Finding the solution

To discuss ideas we had a set of brainstorming meetings very similar to Architectural Kata. On those meetings, we tried to find the root cause of problems we faced, produce example solutions and choose the most suitable solution for us.

Every microservice has his own health check which looks similar to the above

{"bus": "ok", "db":"ok"}

Every time any of the dependencies had a status different than OK, the instance was restarted. This solution worked at a smaller scale but it has a few weaknesses. We decided to make changes in our health checks.

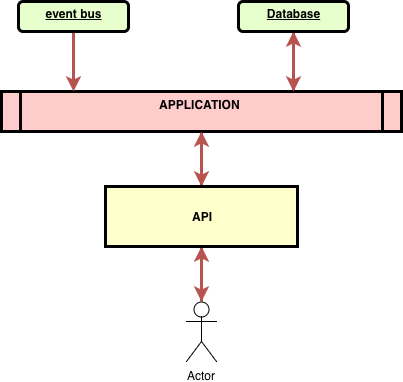

For example, when any of the dependencies started failing the whole instance was restarted. It means that if the application consumes events and writes them to a database and provides a REST API for reads, the whole application stopped working when the event bus experience a failure. In this scenario, the application would be possible to serve the read access.

There were a few ideas on how to deal with this scenario. One of them was green-yellow-red statuses. The meaning of the statuses is as follows:

- Green - the application operates without any problems

- Yellow - the application is experiencing some difficulties but can make his main work

- Red - the application cannot operate normally and requires an intervention

The green-yellow-red statuses were inspired by Elasticsearch.

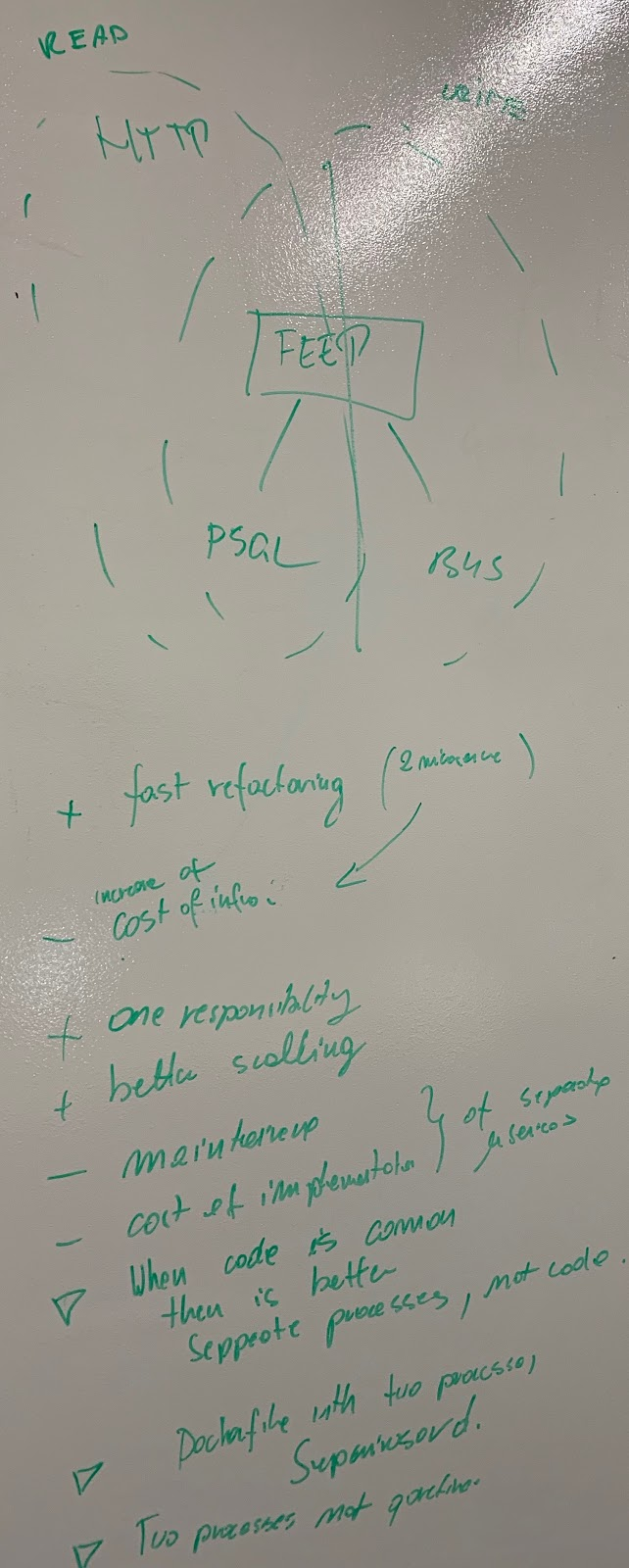

The second idea is to split micro services into separate processes. That would give us good responsibility segregation. One of the processes would accept reads and the second accept writes. They would be scaled separately and have different dependencies.

Another thing we decided to fix was acting differently when any of the dependencies started to experience problems. When any of the services our applications depend on stopped responding, the restart wouldn’t help. Not in 99% of cases. That’s why we started preferring to reconnect over a restart.

Final thoughts

This is only one step of making the infrastructure of steel. System design gave us the opportunity to find the root cause and possible resolutions. We are during a process of experimenting and trying to find the best solution. The journey will never end. We have much more ideas of how to try to minimize any unexpected behaviors. When we’ll have an interesting research about that - we’ll let you know.

What’s your experience in the area? How do you make sure that there’s no single point of failure? Do you use chaos monkey or other tool? Let me know in the comments below.